Today you will…

...Scrutinise/examine Dickens’ devices and techniques of description; further improve analysis and evaluation of texts from our literary heritage.

The 200th anniversary of Dickens’ birth has released a myriad of resources for those interested in studying this great writer or sharing his talents. Students can often name his major works (and may well have seen films or TV adaptations), but will almost certainly need your enthusiasm to highlight Dickens’ specific literary skills amongst other writers they know. Becoming a detective, exploring extracts together and examining clues is an engaging activity that builds the confidence to give an informed personal response; and sharing findings with a new group emphasises the responsibility of everyone to participate. The extracts here have been carefully selected to connect with themes that are still relevant today, whilst also showing how times have changed. Clear, focused outcomes from supported activities will improve the quality of responses, encouraging further literary criticism to emerge.

Starter activity

Looking for clues

Display the following extracts on a whiteboard:

1. “The gruel was served out; and a long grace was said over the short commons. The gruel disappeared; the boys whispered each other, and winked at Oliver; while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery.”

2. ”...he was met by two fellows in a narrow lane, and ordered to stand and deliver. He readily gave them all the money he had, which was somewhat less than two pounds; and told them he hoped they would be so generous as to return him a few shillings, to defray his charges on his way home.”

3. “Thus seyde this olde man

And everich of thise riotoures ran

Til he cam to that tree, and ther they founde

Of florins fine of gold ycoyned rounde

Wel ny an eighte bushels, as hem thoughte.”

4. HERMIA: I am amazed at your passionate words.

I scorn you not: it seems that you

scorn me.

HELENA: Have you not set Lysander, as

in scorn,

To follow me and praise my eyes and face?

And made your other love, Demetrius,

Who even but now did spurn me with

his foot

To call me goddess, nymph, divine and rare,

Precious, celestial?”

Use learning partners or devise small groups to discuss the chronological order in which the extracts were written; encourage students to identify the changes in language, evident over time (and in the process, see how Shakespeare suddenly seems easy compared with Chaucer!)

Pinpointing a list of clues used to make decisions about text externalises student thinking, creates a useful checklist for extension work, and prepares them for sharing their learning and accepting responsibility for engaging with the task. This is particularly important for engaging boys in the idea of accountability or evidence of learning.

Main activities

1. Finding the evidence

For the main activities divide the class into groups by ability, need or focus. Everyone starts in his or her ‘home’ group, working on an extract by Dickens that you have allocated from the selection below (depending on the group, you could use props on the table that match with the extract, or perhaps give them out as a ‘lucky dip’ from a Victorian hat – copying onto different colours makes re-grouping much easier later!) Ask learners to read the extracts together, taking particular notice of Dickens’ devices and techniques of description, his choices of words and the effects these might have on the reader. Get students to annotate their extracts using different colours or symbols for different aspects. Mix up the groups (rainbow the colours) to share the learning and establish similarities or differences in techniques used by the author.

Extract A

The evening arrived; the boys took their places. The master, in his cook’s uniform, stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him…

“Please, sir, I want some more.”

The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupefied astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder; the boys with fear.

“What!” said the master at length, in a faint voice.

“Please, sir,” replied Oliver, “I want some more.”

The master aimed a blow at Oliver’s head with the ladle; pinioned him in his arms; and shrieked aloud for the beadle. The board were sitting in solemn conclave, when Mr. Bumble rushed into the room in great excitement, and addressing the gentleman in the high chair, said,

“Mr. Limbkins, I beg your pardon, sir! Oliver Twist has asked for more!”

There was a general start. Horror was depicted on every countenance.

“He did, sir,” replied Bumble.

“That boy will be hung,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat. “I know that boy will be hung.”

From Ch. 2, ‘Oliver Twist’

Extract B

Chapter 11. I begin life on my own account, and don’t like it.

I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything; but it is matter of some surprise to me, even now, that I can have been so easily thrown away at such an age. A child of excellent abilities, and with strong powers of observation, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt bodily or mentally, it seems wonderful to me that nobody should have made any sign in my behalf. But none was made; and I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone and Grinby.

My working place was established in a corner of the warehouse, where Mr. Quinion could see me, when he chose to stand up on the bottom rail of his stool in the countinghouse, and look at me through a window above the desk. Hither, on the first morning of my so auspiciously beginning life on my own account, the oldest of the regular boys was summoned to show me my business. His name was Mick Walker, and he wore a ragged apron and a paper cap. He informed me that his father was a bargeman, and walked, in a black velvet head-dress, in the Lord Mayor’s Show.

From Ch. 11, ‘David Copperfield’

Extract C

‘I have a long series of insults to avenge,’ said Nicholas, flushed with passion; ‘and my indignation is aggravated by the dastardly cruelties practised on helpless infancy in this foul den. Have a care; for if you do raise the devil within me, the consequences shall fall heavily upon your own head.’

He had scarcely spoken when Squeers, in a violent outbreak of wrath and with a cry like a howl of a wild beast, spat upon him, and struck him a blow across the face with his instrument of torture, which raised up a bar of livid flesh as it was inflicted. Smarting with the agony of the blow, and concentrating into that one moment all his feelings of rage, scorn, and indignation, Nicholas sprang upon him, wrested the weapon from his hand, and, pinning him by the throat, beat the ruffian till he roared for mercy.

‘Shake honds!’ cried the goodhumoured Yorkshireman; ‘ah! That I weel:’ at the same time he bent down from the saddle, and gave Nicholas’s fist a huge wrench; ‘but wa’at be the matther wi’ thy feace, mun? it be all broken loike.’

‘The fact is,’ ....‘that I have been ill-treated… by that man Squeers, and I have beaten him soundly, and am leaving this place in consequence.’

From Ch. 13, ‘Nicholas Nickleby’

2. Finding the evidence

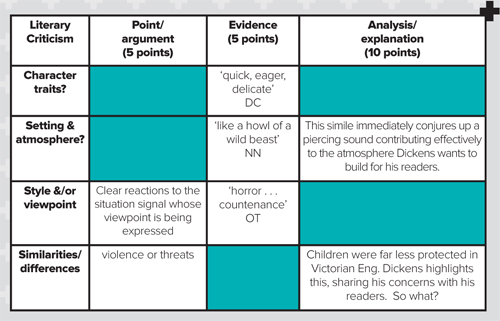

Using grids to help structure note making prevents students being asked to commit their ideas to paper too soon. It is also a supportive activity when transferring analysis into an essay-type response, allowing for planning together and then writing with more confidence independently. The grid above is partially completed for the purposes of differentiation. Teacher modelling or shared reading/writing may be needed, depending on the students’ experience of literary criticism. Less confident pupils could concentrate on the first two aspects of character, setting and atmosphere, whereas gifted and talented learners could be asked to complete all the blanks, or be given a blank grid with no prompts. The point scores are to encourage learners to appreciate the higher value of analysis and evaluation. Often weaker students find and make very valid points, sometimes supported with effective quotes, but fail to analyse sufficiently why these points are true or how the quotation proves the point that they are making.

Peer & self assessment

Once students have written up at least some of the notes independently, ask them to swap books for a www/ebi (what has worked well/would be even better if) assessment. They can then set a target for improvement or ask another group member for suggestions.

3. Making judgements/drawing conclusions

Opposites can often help make sense of unfamiliar writing, and are useful as a writerly device or checklist for readers. Students could return to their ‘home’ groups for this further activity or remain in their ‘away’ groups before returning ‘home’ for a plenary session:

• town/country

• kind/cruel

• poor/rich

• old/young

• good/evil

• educated/ignorant

• male/female

Home learning

Point out to students that Dickens regularly read aloud to his audiences, often practising ‘200 times’ before the performance. Inspired by this, learners could:

• Practise a reading of an extract and share via video/audio or live performance

• Join with others to capture relevant freeze frames for an extract and import into available software, adding a voice over and appropriate soundtrack

• Source film versions of these or other excerpts and share their version of a ‘Dickens Special Film Programme’

Summary

To emphasise the progress made in critical analysis through participation in these activities, students could be asked to write a paragraph immediately following their group discussion, or they could rehearse some ideas together before working independently. An example of this type of more formal writing is included here, embedding the prompts from the activity:

‘When Dickens uses the expression ‘so easily thrown away at such an age’ it stabs at our feelings, creating empathy for the character and shock at such cruel treatment; immediately setting us against the evil that has made this possible.’

Extension: The precise phrase ‘thrown away’ generates, not only movement within the sentence but also a double meaning through the effect of the metaphor and the possibility of a very real physical torture. Furthermore, the everyday saying or idiom ‘thrown away’ draws attention to the acceptability of the society in which this event takes place. In other words, the cruel stepfather can act without fear ‘so easily’.

Any activity that focuses on the analysis and extended explanation rather than device spotting will contribute to improving the quality of literary criticism. The ‘So what?’ question is a useful self -check in developing this type of personal response.

Info

• References for starter activity

• canterburytales.org/canterbury_tales.html extract from Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale 1387 –1400, lines 300 - 330

• online-literature.com/dickens/olivertwist/ Oliver Twist, by Charles Dickens, 1837 – 1839, from chapter 2

• gutenberg.org/ebooks/9611 Joseph Andrews by Henry Fielding 1742 extract from Volume 1 chapter 12

• shakespeare.mit.edu/midsummer/midsummer.3.2.html Act 3 scene 2, A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare – some time in 1590s

• About the expert

Moyra Beverton has over 25 years’ experience of teaching English, coaching and mentoring teachers, improving leadership and management and embedding literacy across the curriculum. She is an active member of NATE, NATE Council & NATE Post-16 committee. uk.linkedin.com/in/moyrabeverton