Telling children which stories are ‘for them’ risks turning them

off literature completely, suggests

Robin Stevens

T

rue story: I actually wrote

my first book before I could

read. Or write. It’s not as

crazy as it sounds; my father

and grandfather were both

academics, so I grew up with books being

created all around me. As a very little child I’d

sit next to my dad and he would scribble on

pieces of paper then give them to his secretary,

who would type it all out. I deduced from this

that the process of ‘making a book’ must be

a kind of mind reading, and I wanted to do it,

too. I got hold of a notebook and pencil, and

‘wrote’, thinking about a great story all the

while. When it was finished, I proudly handed

the ‘book’ to my mum; I wanted her to read it,

for real, and she couldn‘t. It was quite a shock

to realise that there was more I needed to do.

As it happened, I was a little late to read

– at least, compared with what the school

thought should be happening. I was born in

California and we moved to London when I

was three. When I was about five and a half,

my teacher suggested to my mother that

my American accent was holding me back!

Of course, my mother took no notice – and

shortly after that, something suddenly clicked

in my head, and all those squiggles started

to make sense. I remember looking at street

signs, realising that I could understand them,

and getting incredibly excited about making

that connection. And then I went mad; with

nothing stopping me, I read everything.

One of the earliest books I remember

(it feels like it can’t be true, but it is) was

The

Hobbit

. I was lucky, as a kid who wanted to

read, to have parents who valued that. We

moved to Oxford when I was five, and the

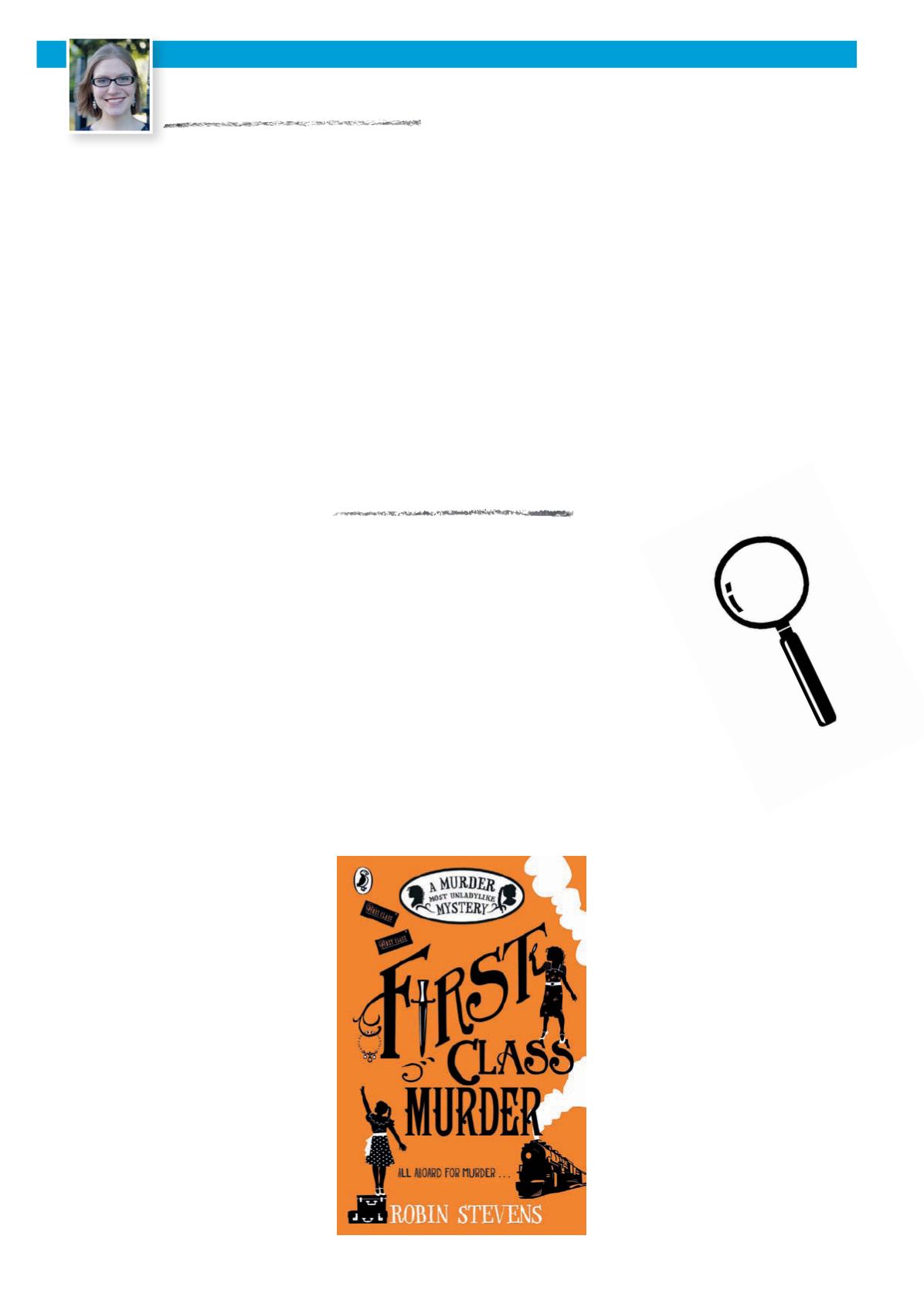

Murder Most

Unladylike is the

book I wish I’d been

able to read when I

was younger.

I really want my books to

be accessible to any kid who

is the right age to enjoy them.

It seems ridiculous to me that we

are increasingly splitting stories by

gender; whom a book is about has no bearing

on whom the book is for. Hazel, one of my

two main characters, is Chinese, and I love

the thought that whenever a white person

reads the book they’re identifying with

her as the narrator, not looking at her as

someone different from themselves. This is

why I believe that boys definitely should read

books about girls and vice versa: seeing the

world through someone else’s eyes is a really

powerful way of understanding them.

Schools work very hard to nurture a love

of reading in their most reluctant pupils – but

sometimes I think adults try too hard to push

particular books on children. The closest I’ve

ever come to a non-positive experience with

books was when my teacher gave a list of

‘advanced’ titles to my mother. My mother is

very rule-abiding, so she’d only allow me the

books on the list itself. I was so furious that

I refused to read

Skellig

in protest – I finally

read it as an adult and realised how stupid I’d

been. All the same, I was turned off reading

it by an well-meaning adult trying to force

a connection that wasn’t there. I think it’s

so easy to do, albeit with the best will in the

world; we need to trust children to find their

own way, in their own time.

library there was a treasure trove, where I

discovered Diana Wynne Jones, Eva

Ibbotson and Terry Pratchett. To read his

Discworld books I needed to venture into the

adults’ section and that felt amazingly cool at

the age of eight.

My mystery series, about a pair of

schoolgirl detectives, is described as Agatha

Christie meets Enid Blyton quite a lot. I’m

very happy with that – both of those are

writers I read hugely as a child. I remember

‘graduating’ from Blyton to Christie, and

wondering where the middle ground was; the

books about kids solving murders. In a way,

“Boys definitely should

read books about girls

– and vice versa”

MY LIFE IN BOOKS

Robin Stevens

TEACH READING & WRITING

89